In the Confederate Infantry, 1861-1864

Submitted by Bobby Brock, Apex, NC. Posted by Myrtle Bridges October 18, 2002

A bit of background information is in order before the main document. William Brock was bom in April, 1826, and raised in Duplin County, according to Aunt Melvina Brock McLaurin, as told to me several years ago as I prepared for this report. I have found only one reference to his father, and none directly to his mother, though I am convinced he had one. In the voter registration of 1902, he lists his father's name as William, also. In the early years of his married life, there was always living near him a Mary Brock, listed as head of household. She was old enough to be his mother, and had a son there the same age as William. (William was a twin) His first child was named Mary. There was a tendency to carry a name into the next generation. It is possible that this was his mother, widowed at an early age. It is interesting that a professional genealogist reached the same speculation in an independent report on the family of John Calvin Brock, older brother to William. William was married to Delitha Haney in January, 1849, in Cumberland County. I have seen no record to specify her parents, but a good many circumstances point to her mother as being Keziah (Hall). Delitha was a sister to Thomas Haney, grandfather of Daisy Tyndall Brock, wife of John William Brock.

|

In 1850, William and Delitha are in Sampson County-he being a farmer with $50 worth of real estate. No record of how he came to own this land. He sold 41 acres to Isaac Williams for $149 on September 3, 1853. I presume that he then relocated to Cumberland County. In 1860 they are in Cumberland County, where they lived the rest of their lives. At that time (1860) there were 2 children Mary K., age 9, and William James, age 5. Mary K. apparently died as a child, as there is no further record other. There is a grave beside him and Delitha, which we presume to be Mary. Their other children were Sarah Delitha and Margaret Caroline. On August 4, 1863, William bought 100 acres from S.R. Hawley for $160. The tract was located "between Beaverdam Branch and a small branch". The sale document specifies that in the event of his death, the land was to go to Delitha. Witnesses were Robert Averitt and Henry Averitt. William sold 54 acres to Thomas Devane for $135 on November 9, 1874. On February 24, 1885, Governor Alfred Scales approved a grant of 25 acres to William for 12 and one-half cents per acre. This land joined that of Patrick Bain, Catherine Bain, and W. R. Williams. William could not read nor write, but Delitha could do both. Judging from pictures, he was of medium size and build. Delitha was a tall, red-faced, and friendly woman, according to Samuel Fann. They lived in a log cabin until she died, sometime after 1900, but before April of 1910. William died in June of 1911, according to the record. He received a state pension for wounds received in the war. He died suddenly, while crossing a fence, looking for a guinea nest, at age 85. He has a military marker, and Annie Brock provided markers for Delitha, Mary K., and Caroline Gautier, who is not buried with her husband. When Aunt Rhoda and Uncle Fuller Fann married in 1913, Grandpa took apart the log cabin and moved it on a wagon and set it up for them to start housekeeping. This house stayed in the Eason family for many years, and Larry Eason gave it to me for the moving, as it was in the way of expanding a field. I now have it on my land in Wake County. The older brother, John Calvin, lived in the Massey Hill/ Hope Mills section. He had 2 wives, sisters Ada and Lucy Jackson. Their descendants are still in the Fayetteville area, as well as in the Grantham community of Wayne County.

The following pages, though not complete in every detail, have the results of many hours of research into the life and experiences of William Brock in the Infantry of the Army of the Confederate States of America. I have visited several of the battlefields where he fought. North Carolina seceded from the Union on May 20, 1861, and joined the Confederacy on May 27. He joined the Army on June 1, at Lock's Creek in Cumberland County. (The place of enlistment is also shown as Silver Run and Bethany on different copies of his muster rolls.) The company in which he was placed was known as "The Cumberland Plowboys". He was placed in Company F of the 24th Regiment, North Carolina Infantry (State Troops), which was organized in July 1861. (The designation of the regiment was changed from the 14th Regiment, North Carolina Infantry (State Troops) on November 14, 1861). Training camps were set up at various locations. His training was at the camp at Weldon, North Carolina. The Confederate Infantryman was in reality a sharp contrast to the neatly dressed gray-clad soldier of the books and movies. To be sure, he was issued one of these uniforms upon enlistment, but he was soon glad to get whatever clothing was available. The hat was usually a black felt of the type often seen worn by backwoods mountain boys in the Disney-type movies. It often served also as a water bucket, and at night as a pillow. Shirts and pants were upgraded as often as possible, many times being taken from dead comrades or even from Yankee Soldiers. Shoes were just added weight to carry, so they were often discarded until cold weather made it necessary to acquire another pair - by the same means as mentioned for clothes. The infantry troops traveled mostly on foot. Barefoot soldiers encountered few problems in their native land, but were in trouble when they invaded the North and found themselves on paved roads. That's why the Battle of Gettysburg happened at Gettysburg - the Rebels planned to get shoes from the shoe making factories there and encountered the enemy when a scouting party went into the town. Around his shoulder was slung a haversack, made of cloth, which contained numerous items - pencil and paper, crackers, harmonica, tin cup - to name a few. A rifled muzzel loader was all he carried in hand. The bayonet was used primarily as multipurpose implement rather than a weapon. Some of its uses included candleholder and cooking utensil. Around his other shoulder was slung his ammunition pouch. A cap pouch was fastened to a belt. One of the most important requirements for service was that a man must have solid teeth. The minie ball and powder were encased in a thick paper covering and the covering was torn off with the teeth and one hand, while the other hand held the rifle ready to be loaded. A seasoned soldier could get off 2 to 3 shots per minute using the cumbersome loading process. Every fifth shot was a "cleaner" to remove residues from the barrel. The Civil War has to be rated as one of the most horrible of all time. The science of weaponry had been more highly developed than the medical sciences. Cannon sent loads of up to thirty pounds for an effective distance of 3 miles or more. The rifled barrel of infantry muzzel loader sent its bullets accurately for several hundred yards. These bullets, or minie balls, were devastating - designed to expand on impact and thus tearing a hole larger than your fist as it left the body. An extraordinarily high percentage of the wounded died shortly because of infection. Many of those wounded in the limbs became amputees, that process being completed very often without any pain killing agents at all. The only comfort available was a minie ball to bite on. Battle casualties were unbelievable. Consider the fact that more than 23,000 men were killed or wounded in a single day's battle at Antietam (Sharpsburg, Maryland). The 24th served directly under Colonels Clarke, John L. Harris, and Thomas Brown Venable. The companies and counties from which the most of the men came were: A - Person; B - Onslow; C - Johnston; D - Halifax; E - Johnston; F - Cumberland; G - Robeson; H - Person; I - Johnston; and K - Franklin. National Archives records state that the 24th Regiment was stationed at White Sulphur Springs, Virginia, in August, 1861, and that the men had not yet received any pay. The same records a-lso state that the Regiment left Weldon, North Carolina on August 18, 1861, and arrived in Anderson, Virginia on September 11, 1861. On September 14, 1861, they marched to the summit of Big Sewell Mountain, Virginia, then to Meadow Bluff, Virginia on September 16. Then on September 24, 1861, marched to Camp Defiance Fayette, Virginia. On October 17, 1861, Regiment marched from Sewell Mountain to Meadow Bluff, Virginia. On November 12, 1861, they marched from Meadow Bluff to Blue Sulphur Springs, Virginia. The Secretary of War ordered the Regiment to Petersburg. On November 26, 1861, the troops left Blue Sulphur Springs and marched to Jackson River Depot, arriving there on the 29th of November. Companies F, G, and H, the last companies to leave, left by rail on December 15th and arrived in Petersburg on the 17th. Absenteeism was very high at this time. Apparently, many were sick or depressed, or both. Many died of measles. To quote the records, "as a consequence of this alarming situation of the health of the men, their constitutions are so shattered as to incapacitate them for any military duty until they recouperate. The place where this can be most effectively accomplished with the least expense to the government is home, and thither they have been sent". The company muster roll for November 30 to December 31, 1861, shows William Brock absent on furlough. The troops returned in January, 1862 to Petersburg and stayed there until February 12, when they marched to Garysburg. From there they marched to Franklin Depot on the 20th. From there they marched on the 21st to Murfreesboro, North Carolina. On the 25th, the Regiment was split up, with companies F and B going to Potecasie Bridge. On the 28th, the company went to Suffolk, Virginia. On orders, the Regiment marched from Suffolk to Murfreesboro, North Carolina, via Boykins Depot, on March 14 and 15. On May 18, the Regiment marched from Murfreesboro to Garysburg, North Carolina, and then to Jackson, North Carolina. The Regiment went to Goldsboro, North Carolina on June 2, 1862. General Lee assumed command of Confederate forces on June 1, 1862. Sixteen North Carolina regiments of Infantry and one of Cavalry were called to reinforce Lee for the Battles of the Chickahominy. General Robert Ransom's Brigade, including the 24th under Colonel Clarke, arrived on June 25th and reported at Richmond and was temporarily assigned to General Huger. Now the men of the 24th would face the enemy for the first time.

During the time of the Seven Days Battle around Richmond (June 25 to July 1, 1862) the 24th Regiment (Col. Clarke) as a part of General Robert Ransom's Brigade, was involved in some minor but sharp engagements with General Philip Kearney's Union forces on the Williamsburg Road, in the neighborhood of King's Schoolhouse. The 24th was listed as one of those "taking the most part in these affairs". These "affairs" took place on June 25 to June 28. On Sunday, the 29th. General Lee had divided McClellon's Union forces sufficiently to throw all he had against them. General John B. Magruder was ordered to advance east on Williamsburg road and attack, with Hill's forces, the rear Union guard north of White Oak Swamp. The 24th was marching down the Charles City Road with General Huger and were to join up with Magruder. Huger changed his mind and continued up the Charles City Road. Again, on the 30th, Huger failed to do as expected, so the 24th saw only light action between June 28 and 30, 1862. Robert Ransom's brigade, including the 24th, was part of Magruder's forces, after Huger finally came in place on July 1 for the battle at Malvern Hill. But Magruder was delayed and did not attack (at Savage's Station) until after sunset, just as Hill retreated with his beaten brigades. Confederate artillery was to shell the Union line ahead of the infantry attack, but failed to do so. Seeing this situation, Lee cancelled the infantry attack, but they did not get the word. General Hill described Magruder's assault: "I never saw anything more grandly heroic than the advance after sunset of the nine brigades under Magruder's orders. Unfortunately, they did not move together and were beaten in detail. As each brigade emerged from the woods, from fifty to one hundred guns opened upon it, tearing great gaps in its ranks; but the heroes reeled on and were shot down by the reserves at the guns, which a few squads reached... Not only did the brigades which were engaged suffer, but the inactive troops and those brought up as reserves, too late to be of any use, met many casualties from the frightful artillery fire which reached all parts of the woods. Union General Porter tributes the attack: "As if moved by a reckless disregard of life, equal to that displayed at Gaines' Mill* with a determination to capture our Army and destroy it by driving it into the river; regiment after regiment rushing at our batteries; but the artillery ... mowed them down with shrapnel, grape, and canister, while our infantry, withholding their fire until they were within short range, scattered the remnants of their columns. The havoc made by the rapidly bursting shells ---were fearful to behold. Pressed to the extreme as they were the courage of our men was fully tried. The safety of our Army - the life of the Union - was felt to be at stake." Seventy-two men of the 24th were killed, wounded, or missing during this their first week of fighting. In a report about Company F of the 24th filed on the Cumberland County home page by William Bullard, there is an interesting reference to William Brock in this battle: "an incident worthy of mention occurred in this battle. Private William Brock could never keep exact step in march, due (the boys said) to the length of his feet, so one or another officer often called out "keep the step, Mr. Brock". In the hot test of the fight, this fine soldier called out "Don't get excited, boys, and bite off the ball of your cartridges. Say, boys, I don't hear anybody calling "keep step Mr. Brock". The Regiment was stationed on the City Point Road, near Petersburg until the 19th of August, then marched toward Richmond and bivouacked near Richmond until the 23rd when it marched to the Pontoon Bridge on the James River.

Immediately after the Rappahannock Campaign, General Lee, desiring to inflict further injury upon the enemy ... decided to enter Maryland. He knew that his Army was feeble in transportation, the troops poorly 1 Battles and Leaders, II, page 394 2 Batt1es and Leaders, II, page 418 *Gaines' Mill, or Cold Harbor, earlier in the campaign was described as one of the hottest of the war., supplied with clothing, and thousands of them destitute of shoes. Still he felt that his troops, seasoned by active service and filled with enthusiasm and confidence ... by their successes, could be relied upon for much self-denial and arduous campaigning. The prospect of shifting the burden of military occupation from Confederate to Federal Soil and keeping Federals out of the South at least until winter prevented their re-entering, was alluring. Between September 4 and 7, 1862, the Confederate Army crossed the Potomac at Nolands Ford near Leesburg and encamped in the vicinity of Frederick City, Maryland. Included in this force was General Ransom's Brigade of four North Carolina Regiments, including the 24th under Colonel J. L. Harris, under General W. H. T. Walker. Ransom's Brigade was ordered to leave the Monocacy River where, with Walker's Brigade, it had been trying to break the aqueduct. It was anticipated that as Confederates advanced. Federal garrisons at Harper's Ferry and Martinsburg would be withdrawn. So Walker's troops, along with those of General Jackson and General McLaws were sent to invest these places. Walker was to occupy Loudoun Height, across the Shenadoah from Harper's Ferry, as directed in Lee's Special Order 191. This order fell into the hands of Union General McClellan, after a Yankee soldier found it wrapped around 3 cigars at an abandoned Rebel Camp. Southern troops marched away from Frederick on September 10-12. Walker's men crossed the Potomac on the night of the 10th, rested on the 11th, and reached the foot of Loudoun Height on the morning of the 13th. On the 14th, Walker, Jackson, and McLaws began to batter at the defenses of Harper's Ferry. Jackson was in command and mapped the strategy. On the morning of the 15th, Walker's guns set rolling the echoes of Loudoun Height, having been forced to wait until a heavy mist lifted to reveal their target. Harper's Ferry was surrendered (by Union General Julius White) to Jackson with only light losses to the Rebels, after only an hour of battle. Confederates made a good haul - 13,000 small arms, 73 cannons and about 200 wagons and about 11,000 prisoners. As Walker's column came over the Shenandoah - on their way back to Lee, there was much grumbling because Jackson's troops had devoured or appropriated all the booty.

After a brief rest, the troops of Walker and Jackson started to join General Lee at Sharpsburg where he was engaging a vastly superior Army with the Potomac at his back. By a severe night march, they reached Sharpsburg about 16 miles away, about noon on the 16th. General Walker's troops were first placed on the right of General Longstreet. While in this position the 24th assisted Georgia Sharpshooters in preventing Union troops from crossing Antietam Creek at Snavely's Ford. The terrain here is somewhat rugged, with slopes ranging up to 30-40 percent. A little before 10:00 a.m. on the 17th, they moved to reinforce the left. Walker's troops charged headlong upon the left flank of Sedgewick's lines, which were soon thrown into confusion. General Palfrey, a Federal participant, said in his Antietam and Fredericksburg, nearly 2,000 men were disabled in a moment. The Confederates did drive the enemy before them in maghificient style; they did drive them through the woods, but (some of them at any rate) over a field in front of the woods, and over two high fences beyond and into another body of woods over half a mile distant from the commencement of the flight. In this rout of Sedgewick, the N.C. Regiments were destructive participants. Walker's division (containing the 24th Regiment) being the first to start the rout. General Ransom's Brigade drove the enemy from the woods in its front and then - held for the rest of the day, that important position, called by General Walker the key of the Battlefield, in defiance of several sharp, later infantry attacks. Ransom's men endured a prolonged fire from the enemy's batteries on the extreme edge of the field. General Walker reports, True to their duty, for eight hours our brave men lay upon the ground, taking advantage of such undulations and shallow ravines as gave promise of partial shelter, while this fearful storm raged a few feet above their heads, tearing the trees asunder, and filling the air with shrieks and explosions, - realizing the fearful sublimity of battle. Colonel M. W. Ransom, of the thirty-fifth regiment, brother of General Robert Ransom, was temporarily in command of the brigade while his brother was on official duty elsewhere. The battle of Antietam was called the bloodiest single day's battle of the entire war. Twelve thousand five hundred Federal and 10,750 Confederate soldiers were killed or wounded. In the entire Maryland Campaign, North Carolina losses were as follows: 335 killed, and 1,838 wounded. During the night and the next morning. General McClellan was joined by reinforcements numbering more than his losses. Lee received none. Lee remained in position through the 18th, and considered another attack. But that night, he was pursuaded by Jackson and Longstreet to withdraw and cross the Potomac to the Virginia side. Lee's army recuperated for about six weeks near Winchester, in the Shenandoah Valley. In late October, McClellan brought his army into Virginia. Lee immediately placed Longstreet's troops, including the 24th, at Culpeper to check McClellan's advance. Lincoln replaced McClellan with Burnside, who marched his army to Fredericksburg but the confederate troops were placed and waiting by the time Burnside was ready to cross the river in late November.

On December 12, 1862, General Lee placed his army on the hills around Fredericksburg, having learned that General Burnside had three divisions stretched along the North side of the Rappahannock River -waiting for pontoon bridges to be completed so that he could cross over and attack. Lee's army, on the south side, extended parallel to the river a distance of about 3 miles from a point across from Falmouth to Hamilton's crossing. Longstreet convnanded the left; Jackson the right. General Lee was positioned atop a high hill where he had a very superb view of the direction where the Union troops were. At this point, he had positioned a number of mammoth cannons which fired a thirty-pound load. A wide, open plain lay between Jackson's line and the river, across which lay the Union forces under General Burnside. It was from his vantage point that General Lee uttered It is well that war is so terrible - we should grow too fond of it as he watched Union 12 troops march in picture book precision to a weak spot in the Confederate line, temporarily pierce it, only to be pushed back when Jackson hurried in his resources. A bright sun burned the fog away on the morning of the 13th. Longstreet first thought that federal forces would bring heaviest attack on the Confederate right (Jackson), but it soon became apparent that the main assault would be to Jackson's left. He then summoned Ransom's division ( 24th N.C. regiment, Lt. Col. J.L. Harris) from reserve and placed it to guard Mayre's Heights. The special care of that part of the front was assigned to Ransom. The previous night, most of Tom Cobb's brigade had been moved down to the Sunken Road to relieve Barksdale's men. On Cobb's left was placed the 24th. These troops were sheltered behind a stone fence, a part of which still remains and can be seen just north of the Fredericksburg National Military visitor center. The wall runs beside the Sunken Road, at the base of a high hill. These troops had a pet rooster, trained to crow on signal. The signal would be given and the rooster would crow just before each volley by the sharpshooters. Summers' division made desperate attempts to carry Mayre's Hill, the salient point of the Confederate left. The heroic defense of the Confederates behind the stone wall will live perpetually. (1) At the opening of the attack, this wall was held by the gallant brigade of General Thomas Cobb and by the 24th. As the fighting grew hotter, Ransom sent in more N.C. regiments. At this point where the 24th fought, occurred some of the heaviest fighting of the battle. (1) Battles and Leaders II. General Burnside made a terrible mistake in trying to rout the Rebels at Mayre's Heights. He hurled brigade after brigade at the stone wall. As one soldier described it, they reach a point within a stone's throw of the stone wall - that terrible stone wall. No farther. They try to go beyond but are slaughtered. Nothing could advance farther and live. Darkness brought a stop to the charge. That night, many of the wounded froze to death as they lay on the snow covered ground. Federal losses around 5,500. North Carolina losses were: Killed - 173; wounded -1,294. This battle was termed a terrible defeat of the North by World Book Encyclopedia.

Soon after Fredericksburg, conditions in North Carolina were getting worse. Federal General Foster had successfully raided Kinston and -Goldsborough. It was felt that a Great Federal Fleet was to capture Wilmington, and that North Carolina must be reinforced substantially and at c once. On January 3, 1863, General Lee ordered Ransom's brigade from Fredericksburg to North Carolina. The troops arrived in Petersburg on the 7th, left on the 16th by train and arrived in Goldsboro, North Carolina on the 17th. They left Goldsboro on the 19th and marched to Kenansville, arriving on the 21st. They apparently camped there until February 23rd, when they marched to Magnolia, took the train to Wilmington, arriving there on the same day. In mid-March, 1863, General D. H. Hill and General Longstreet planned an offensive move against Federal troops in New Bern. They both requested men and guns from General Whiting, but he refused. Even so. Hill and Longstreet made a feeble and unsuccessful attack against New Bern. Among the reasons for failure heaviest blame of all was put on Whiting for not sending Ransom's brigade from Wilmington. On March 30, the siege of Washington, North Carolina was begun by General Hill. To cooperate in this seige. General Whiting sent Ransom's brigade from Wilmington though he maintained that by so doing he sent two-thirds of his infantry and all that was disciplined and efficient. The seige seemed to cycle between hope and despair, but on the whole was not successful and was abandoned on April 16, 1863. This was mostly artillery fire. Troops mostly foraged corn and bacon. In mid-May 1863, Union General Foster felt that he could make an effective demonstration against the inland stretch of the Atlantic and North Carolina Railroad. His first move was to order Col. J. Richter Jones to endeavor to surround the enemy at Gum Swamp a Confederate outpost about 8 miles below Kinston. This rout took place on the 22nd with Federal troops on three sides. Therefore, the Confederates retreated to the direction not occupied by Union Troops, which happened to be an almost unpenetrable swamp. The 24th was apparently involved in this skirmish, as General Robert Ransom was involved. The Confederates' humiliation at Gum Swamp was partially off-set by reinforcement troops arriving and driving the Federals back toward New Bern to a stalemate skirmish at Batchelder's Creek. In late May, Lee transferred many troops from N.C. to Va. See letter from Lee to Hill, dated 5-25-63 P.H. papers. State Library at Richmond, Va. The Regiment took a train to Petersburg, Va. on May 30, 1863, arriving on June 1st. The next day they took the cars to Ivor Station, marched to Blackwater Bridge, left there on the 12th and marched back to Ivor Station, boarded the train and went back to Petersburg. After more movement in that area, they marched to camp near Richmond on June 25th. Robert Ransom was promoted to Major General in May 1863. On June 15, 1863, Colonel M. W. Ransom, brother of Robert Ransom, was promoted to Brigadier General and took command of the brigade formerly led by Robert Ransom. On July 27, 1863, the 24th was involved in turning back a Federal attempt to destroy the bridge of the Wilmington and Weldon Railroad over the Roanoke River at Weldon. This skirmish involved only about 200 Confederate Infantrymen with 2 pieces of artillery; whereas the Federal troops numbered about 5,000, including a brigade of Cavalry and nine pieces of artillery. On July 28, 1863, General M. W. Ransom, with 4 companies and a section of artillery, at Jackson, North Carolina, routed a cavalry force of 650 men. No mention of which companies. The Regiment moved by rail from Weldon, North Carolina to Tarboro, North Carolina on October 28th. On November 1st, companies B, F, H, and I marched to Greenville, North Carolina. In November and December, 1863, the Regiment was at Hamilton, North Carolina (about 25 miles NW of Williamston, near the Roanoke River) In late December, 1863, companies E, I, and F went near Plymouth to ambuscade a regiment of union cavalry. But it rained so much the powder and ammunition got too wet, so they gave up and went back and rejoined the regiment.

At end of 1863, Eastern North Carolina was in deplorable condition. Considerable plundering was taking place with horses and mules being special objects of plunder. Pianos and other costly furniture were siezed and sent North, while whole regiments of bummers defaced and ruined the finer homesteads in search of treasures. Many Negroes swarmed about, sent back by Federal troops to recruit other Negroes into the Union Army. In order to alleviate this situation and to capture much needed supplies at New Bern, a force of some magnitude was sent to North Carolina at the opening of 1864. General George E. Pickett, with a division, was sent from Petersburg to help troops already there. In Pickett's command was General M. W. Ransom's brigade, of which the North Carolina 24th Infantry was a part under the leadership of Colonel Clarke. On January 30, 1864, under Lee's orders. General Pickett set out from Kinston to attack New Bern. Part of Ransom's brigade was on this operation, but I'm not sure whether or not the 24th Regiment was included. This expedition was not successful in its objective. On the night of February 2, 1864, Ransom's men withdrew from Brice's Creek at New Bern to Pollocksville. The road they took was one vast mudhole about the consistency of batter and about shoe-mouth deep as a general thing, with frequent places of much greater depth. Boxed pine along the road were lighted, since the night was very dark. On March 9, 1864, General Ransom with his brigade and a Calvary force drove the Federals from Suffolk and captured a piece of artillary and quartermaster stores of much value. Judge Roulhac in his Regimental History described the battle as a most exciting little affair in which Negro soldiers were faced for the first time by his troops.

Plymouth, North Carolina was held by General H. W. Wessells with a Union Garrison of 2,834 men. Confederate General R. F. Hoke had been selected to lead an expedition to capture the town and wished naval assistance. He rode up river to inquire of Commander Cooke (who was building an ironclad at Edward's Ferry on the Roanoke) when he could get cooperation of the boat. At first, Cooke said it would be impossible to have the boat ready in time, but Hoke persuaded him and got his promise to take his boat to Plymouth finished or unfinished. As promised, Cooke started down the river on April 18, finishing work on his boat (which he named the Albermarle) and drilling his men as he went. Action also started at Plymouth early on the 18th, about 6:00 A.M., Ranson's men demonstrated in force against the enemy line east of Fort Williams. This attack, in the face of artillery fire that lighted the site, took the Confederate within a few hundred yards of the enemy works. But such a heavy dose of iron was thrown at them that around 1:00 A.M., they withdrew to their position of the morning. In the early hours of the 19th, the Albemarle dropped down the river and passed the fort at Warren's neck, under a furious fire. In the rear of Fort Williams, the Albemarle rammed two Federal gunboats, the Southfield and the Miami. Southfield, with 9 feet of the Albemarle's prow in her side was at the river bottom in 10 minutes. Other gunboats retreated, being chased by the Albernarle. This action gave General Hoke a vulnerable point of attack on the river side of Plymouth. Hoke had invested the town with his own brigade, the brigade of Ransom (which included the 24th) and one of Pickett's under Terry. In late afternoon of the 19th, Ransom's brigade was ordered to cross Conaby Creek to the east, go around 4 to 5 miles to the Columbia Road, and attack the town from that direction. It was midnight by the time they were in position so they were allowed to rest until daybreak. At daybreak on the 20th they started the attack advancing first at quick time, then at double time. They over ran the fortifications and chased the enemy into Fort Williams. Cooke returned with the Albermarle and opened fire on Fort Williams. Then Hoke moved Ransom's brigade around to attack from the river side. Ransom's men gallantly stormed the works, meeting not only the usual artillery and infantry fire, but encountering hand-grenades thrown from the works. On al1 sides the Confederate forces closed in, and after a struggle in which both sides fought only as seasoned soldiers are apt to fight, the town with its garrison of nearly 3,000 men and 25 pieces of artillery was surrendered. The Confederate Congress passed a vote of thanks to General Hoke and Commander James Cooke and the officers and men under their command, for the brilliant victory over the enemy at Plymouth. This gallant deedawakened great enthusiasm in the state, for it was now hoped that North Carolina might be cleared of invaders."

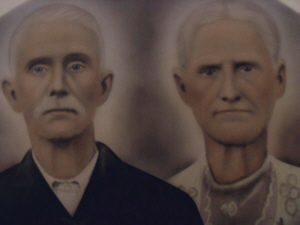

According to a muster roll of Co. F of the 24th N.C. Regiment, dated July 8, 1864, William Brock was "disabled by wounds at Plymouth, North Carolina, April 20, 1864". Another muster roll covering the period June 30 to December 31, 1864 states that William Brock was discharged and final statement given August 29, 1864. His name appears on a Roll of Honor of Co. F, 24th Regiment, North Carolina troops. Anyone who is able to amend or clarify this information is encouraged to do so. Bobby G. Brock (lineage-Bobby G. Brock-1941- George Adam Brock-1892-1968 William James Brock-1855-1934 William Brock-1826-1911) Prepared original January 6, 1970 Updated October 25, 1972 Updated January 1, 1976 Updated September 11, 1995 Updated December 28, 1999 Updated September 1, 2002 Ref: Confederate Military History, Vol. 4, pp. 218-224, Evans, C.A.William Brock and children: William James Brock; Sarah Delitha Brock House; Margaret Caroline Brock Gautier (photo ca. 1905-1910)