JOSEPH JONES

ca 1730-1800

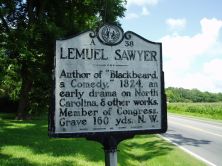

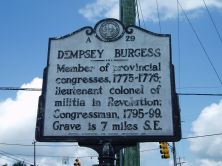

IT TOOK forty-two years for the inhabitants on the northeast side of Pasquotank River to realize their ambition to become a separate county. By an interesting coincidence the three families who have probably contributed most to the history of the northeast side—Sawyer, Burgess and Jones—all played a part in the efforts made to accomplish this cherished ambition. The attempts of Caleb Sawyer in 1735 and of William Burgess in 1744 have already been noted, and we have also learned that both bills were defeated because they contained a provision providing for the same rights and privileges as the other counties in the Albemarle, which meant five representatives in the assembly. The newer counties which had been created were allowed only two representatives, and the governor opposed what he considered to be an inequitable allotment of representation.

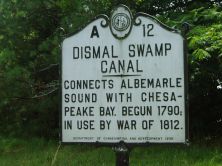

This objection was eliminated, however, by the State Constitution, adopted in December of 1776, which set up two houses in the legislature, the senate and the House of Commons, and each county was allowed one senator and two representatives. Joseph Jones, a resident of the northeast side, was elected the first senator from Pasquotank for the first session of the State Legislature, which met in April of 1777. On April 19 Senator Jones moved for leave to prepare and bring in a bill to divide Pasquotank into two counties, one on either side of the river. The bill was read the necessary three times, passed and was ordered to be engrossed on May 9. The name was chosen, according to a well-established tradition, in honor of the Earl of Camden, Sir Charles Pratt. News of a speech, which he had made in Parliament defending the colonies, arrived while the new county bill was pending. Following is the measure which brought Camden into being: “I. Whereas by Reason of the Width of Pasquotank River, and the Difficulty of passing the same, especially in boisterous weather, it is extremely inconvenient for the Inhabitants who live on the North East side of said River to attend Courts and other Public Business in the County of Pasquotank; For Remedy whereof: II. Be it therefore Enacted by the General Assembly of the State of North Carolina, and it is hereby Enacted by the Authority of the same, that all that part of Pasquotank County lying on the North East side of the said River, and a Line to run from the Head of the said River a North West Course to the Virginia Line, shall be, and is hereby established a County, by the name of Cambden.”

If the term statesman can be applied to any person who has matured in Camden, Joseph Jones would probably qualify. Beginning with 1760, he served in the Assembly seventeen years as a member from Pasquotank, and one year as a senator and one as a representative from Camden, after the formation of that county. Referring to the Provincial Congress held at New Bern in 1775, W. L. Saunders, editor of the Colonial Records, states, “It has never had a superior from that day to this.” To illustrate the caliber of the men assembled he mentions Thomas Jones, Joseph Hewes, John Harvey and Joseph Jones, all from the Albemarle counties. Walter Clark, editor of the State Records, also cites the Camden man as being one of the state leaders during the Revolutionary period. According to a local tradition, Jones came within one vote of being elected Speaker of the House when John Harvey was chosen for that position. Jones’ long tenure in the Provincial Assembly had given him both parliamentary experience and intimate acquaintance with political leaders in the state.

Some of the measures with which he was connected in the legislature have a significant relation to the times. For example, in 1766 he presented a certificate from the inhabitants of Pasquotank County setting forth the many great hardships “the said inhabitants as well as several other inhabitants of this province indure, for want of Paper money and other currency.” This lack of money made buying and selling a cumbersome and tedious process. If a man wished to sell a barrel of pork, for instance, a prospective buyer having no money might wish to offer an amount of tobacco equal to the purchase price. If the owner of the pork happened to desire clothing or food, but had no need of tobacco, he made no sale or if he took the tobacco he continued his search for someone having the articles desired. As a matter of fact, a large amount of the business transacted during the colonial period was on a barter basis. To facilitate matters, laws were passed assigning definite values for trading purposes to certain staple products, such as pork, tobacco and corn; indeed we find one disgruntled taxpayer reporting that he had paid his taxes with “tallow and hog’s lard.”

In 1769 Jones was a member of a committee which investigated Thomas Person of Granville County when an unsuccessful attempt was made to oust him from the Assembly because of his participation in the insurrection of the Regulators in the Orange and Alamance Counties region. Sentiment in the easternmost counties was generally antagonistic to the Regulators, and Governor Tryon had used the militia from this area to quell the insurrection. During the same session Jones was in favor of prohibiting shipments of corn from the province “due to the great scarcity of Indian corn likely to ensue.” Then as now storms sometimes caused heavy damage to crops.

His activities increased with the approach of the Revolution, one of the most spectacular instances of his participation being the clash with the Tory Thomas McKnight, as an outcome of the Provincial Congress held in New Bern in 1775. McKnight was one of the wealthiest members in the province, owning thousands of acres in Currituck and Pasquotank Counties and elsewhere, a shipyard at Indiantown, and a partnership in a commercial enterprise at Norfolk. At the time he was clerk of the court in Pasquotank, but he attended the Congress as a delegate from Currituck. When a move was made to express approval of the actions of the Continental Congress held in Philadelphia the past September, McKnight was the only one, at least openly, who refused to subscribe his approval. His stand aroused considerable resentment among the delegates who in consequence passed a resolution of condemnation on April 6, stating in part “that from the disingenuous and equivocal behavior of the said Thomas McKnight it is manifest his intentions are inimical to the cause of American liberty; and we do hold him up as a proper object of contempt to this Continent, and recommend that every person break off all connections and have no future intercourse with him.” Three of the delegates from Currituck and two from Pasquotank made a written protest in McKnight’s behalf and withdrew from the Congress, but to no avail. There was one very influential member from Pasquotank who aligned himself strongly with those denouncing McKnight, and he was Joseph Jones. He was largely responsible for the treatment accorded McKnight, in the opinion of the latter, and on June 21, a long letter defending himself and addressed to Jones was published in the Virginia Gazette. Jones was unrelenting in his attitude, however; he evidently felt that the time for quibbling had passed and that every man must throw his lot entirely with the colonies or be counted as an enemy.

In September, 1775, he was named a member of the Provincial Council of Safety for the District of Edenton, but his prodigious activities are best indicated by a description of the committees on which he served during the meeting of the State Legislature in 1777. The purposes or tasks of some of the more important committees were, using the phraseology of the minutes: To receive and consider all applications relative to military matters; to consider what Magazine of provisions and military stores it is necessary should be laid up, both for the Continental Army and for the State Militia; to consider the Expediency of stationing a body of militia on our Frontiers to protect the inhabitants of this State against the Indians; to devise ways and means to remove the enormous expense arising by the supernumerary officers in the Continental Regiments; to establish courts of justice; and to consider what price shall be allowed to commissioners for rations. After 1778 he served one year in the lower house during the session of 1782. At this time he was one of those placed in nomination as a delegate to the Continental Congress but was not elected.

As a result of his business enterprises Jones amassed a fortune. Among other undertakings he was a merchant and one of his chief interests seems to have centered around exportation and importation of commodities. Before the Revolution he conducted his trading enterprises chiefly from the developments at Old Trap Bay and Milltown near Shiloh. After the war he concentrated his interests at Plank Bridge near Camden, and at River Bridge in the vicinity of South Mills.

At Plank Bridge his efforts to establish a town met with considerable success for a while. From Murden’s landing all the way up Sawyers Creek to the Bridge appeared many wharves and storehouses. Plank Bridge was made a port of entry. In his Travel Memoirs the Duc de la Rochefaucauld-Liantour comments upon the activity of the location when he visited there in 1798 with Talleyrand, although it must be confessed he was greatly confused in his geography since he located Plank Bridge as being near Wilmington. A town was laid out on the north side of the Bridge and named Jonesborough in honor of the founder. In a deed which Jones made on July 17, 1792, to his daughter Sally and her husband Michael Fennell, the description of “certain Lotts in the Town of Jonesborough on Sawyers Creek” reads in part as follows:

“Lott No. 34—beginning on the north side of State Street, running north 87° west to Second Street thence running south 3° west to Market Street.” The project, however, was doomed to failure. The shipwrights were continually building vessels of heavier tonnage so that a greater depth of water was increasingly necessary. The Town of Redding, which was to be renamed Elizabeth City, had already been laid out at a site below on the river where deeper water could accommodate the larger craft, and to this location commercial craft were gradually but inevitably attracted. Today not a vestige of the Town of Jonesborough remains, and of the numerous warehouses and wharfs once standing there is visible only an occasional rotting pier in the waters, which have resumed their immemorial dark stillness.

Upon the formation of Camden County in 1777 Jones was naturally one of the five commissioners named by the legislature to set up the details of county government, select a site for the courthouse and attend to other initial requirements. His residence was used as a meeting place for the commissioners. It so happened that his dwelling was located almost in the geographical center of the county, and the site selected for the courthouse was directly oppoiste his manor plantation. No attempt was made to erect a building, however, until 1782, very probably because the energies of this highly patriotic county were entirely devoted to participation in the struggle for independence. In that year an acre and one quarter, the site previously selected, was purchased from Thomas Sawyer and his mother Margaret, and construction of a courthouse, jail, and stocks was authorized. According to tradition, Jones’ residence also served for the sessions of the county courts, he being one of the county justices as he had been also in the county of Pasquotank. Thus he was closely associated with the beginnings of Camden County in various capacities.

He was a member of a family which had long been active in the life of the northeast side. His father Isaac was a substantial planter; his uncle Nehemiah had been a captain in the Pasquotank militia during the French and Indian War period; his great-uncle Jarvis Jones had held the rank of major in earlier colonial wars. The military tradition was continued by his youngest brother, Timothy Jones, who was a lieutenant in the Continental Line.

Source: Three Hundred Years Along the Pasquotank, pages 101-105 by Jessie F. Pugh (1957).

The name Forke Chapel continued to be used until 1800 when the present name was adopted, presumably for Elisha McBride, one of the founders. Prominent families associated with the church include members of the Halstead, Pearce, Taylor, Sawyer, Abbott, Forehand, Gordon, Jones, McCoy, McPherson, Spence, Whitehurst, and Williams families.

The name Forke Chapel continued to be used until 1800 when the present name was adopted, presumably for Elisha McBride, one of the founders. Prominent families associated with the church include members of the Halstead, Pearce, Taylor, Sawyer, Abbott, Forehand, Gordon, Jones, McCoy, McPherson, Spence, Whitehurst, and Williams families.