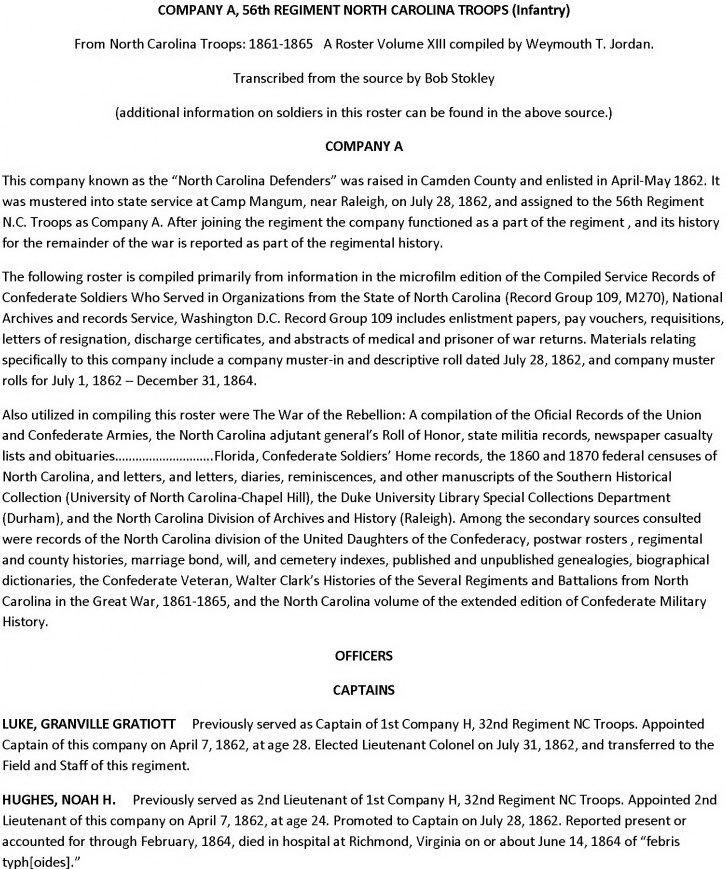

MAJOR WILLIS BURGESS SANDERLIN

1829-1900

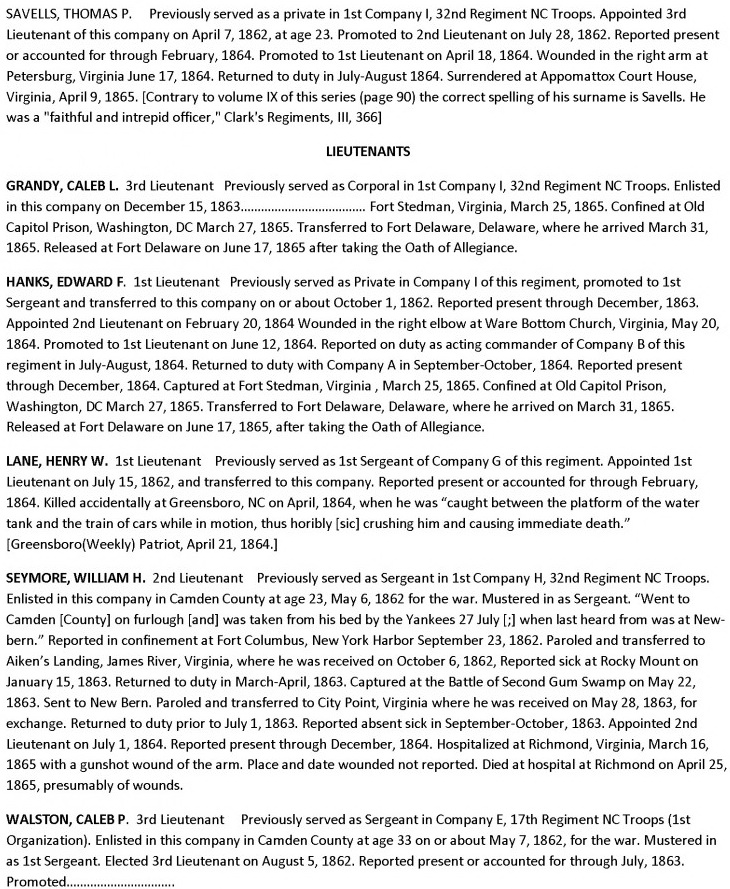

CAPTAIN WILLIAM PERKINS WALSTON

1838-1914

THE MOST EXCITING CHAPTER in the history of this county will probably remain an untold tale in large part. The Home Guards, the military units formed for the purpose of defending local or “home” territories, were not mustered in the service of the Confederate States and no records were sent to Richmond, though these troops were subject to orders by the Confederate generals. Moreover, the Camden company by force of circumstances conducted its operations as secretly as possible. During the war years, beginning with the summer of 1862, Federal troops were quartered hereabouts and in Camden the efforts of the Home Guards were faced with additional hazards by the presence of a considerable body of Union sympathizers. For purposes of secrecy, therefore, written orders and reports were avoided by the Confederate defenders; and as a consequence definite information of their perilous activities is usually lacking.

On the other hand, the service records of those soldiers who formed a part of the regular Confederate Army were lodged in the general files in Richmond and thereby we know the names of the men and also the events, generally speaking, in which they participated. Company B, which was incorporated with the Thirty-Second Regiment, according to Confederate war records, was the first Camden unit to be recruited following the fall of Fort Sumter in April of 1861. A majority of the enlistments were dated in May and practically all were from the northern half of the county, less than a half dozen being from the southern end. The four captains of this command during the war period were Joseph G. Hughes, James W. Ferebee, Joseph C. Rudds and James E. Hodges, in the order given. The other commissioned officers, listing them only in the highest rank which they attained, were First Lieutenants John S. Morgan and William B. Overton, and Second Lieutenants Addison P. Cherry, William Civils, John S. Hodges, George W. Nixon, Richard H. Parker, James H. Sawyer, and Joseph H. Stevens. Disease and battlefield casualties were the causes of frequent changes in personnel. Sergeants shown on B’s complete roster were Robert R. Bullock, Oliver Cherry, Joseph M. Gregory, Job C. Hughes, William P. Miller, Enoch Nash, David T. Pritchard, James E. Radford and Miles Spence. Eight corporals listed were Benjamin B. Burnham, Samuel J. Dunn, James W. Etheridge, James A. Henly, William B. Jome (Jones?), David McCoy, Benjamin C. Pritchard, and J. T. Sawyer. J. L. Frensley and Richard C. Perkins were elevated from privates to the rank of captain in a commissary corps, and David T. Pritchard is said to have been promoted in the field to the rank of captain at the Battle of Bloody Angle near Spottsylvania Court House. Of especial interest are the four men who enlisted as musicians; two, Morgan and Rudds became commissioned officers in the company; John Jacobs was made staff officer in charge of regimental music; and Charles Consolvo, then a stripling, was later to build the famous Monticello Hotel in Norfolk. Family names represented in greatest numbers were Sawyers, six; Brights (Brite), five; McCoys, four; and Etheridges, three. According to notations on the roster some of the principal campaigns and battles in which the company participated were Suffolk, Lynchburg, Petersburg, Spottsylvania Court House, and Gettysburg, the greatest number of casualties being shown for the last-named engagement.

According to the records, then, the first men to enter the conflict were those enrolled in Company B. There is, to be sure, a well established tradition in South Camden that a group of volunteers from this area were among the prisoners captured at Hatteras when that port fell to Federal forces in August of 1861. Apparently there is no documentary evidence to support this belief, although a number had probably volunteered.

During the summer of this same year, 1861, eight recruits from Camden joined a Pasquotank company which, as a part of the Eighth Regiment, surrendered to Federal forces when Roanoke Island was captured February 8, 1862. One of this county’s soldiers who became a prisoner of war was John K. Abbott, commissary field officer. Since an exchange of prisoners was soon effected, all were back in active service without much delay. A year later nine more men crossed over to enlist in another Pasquotank unit which was incorporated with the Fifty-Sixth Regiment, as also was Camden’s Company A.

Almost one third of the combat strength of Company A, organized in South Camden during the months of April and May, 1862, consisted of transfers from Henderson County, which were added in July when the command was detached for military duty in the field. Altogether this organization was to have four captains, who were G. Gratiot Luke, Noah H. Hughes, Caleb P. Walston and Thomas P. Savills. The two subordinate officers who hailed from this locality were Second Lieutenants Caleb L. Grandy and William H. Seymore (Seymour). All of the sergeants were natives of Camden and the roster lists the following ten who had a tour of duty during the war years: Wilson Beals, K. R. Bell, G. L. A. Berry, Loyal Berry, Nicholas S. Burgess, Noah C. Burgess, George Ferrell, Thomas Harrell, Calvin Johnson and Peter Tumbler. Noah C. Burgess was later transferred to H Company. Six corporals were designated: Isaac Berry, William Clingman, Marshall Jennings, James Sawyer, Samuel Smith and Jesse Wood. The names occurring most often in the company roll were as follows: Sawyer, five; Mercer, four; Berry, Burgess, Gallop and Johnson, three each; and two each for Bell, Dozier, Forbes, Garrett, Jones, Torksey and Wright. Some of the engagements in which Company A saw action were Green Swamp, Battle of the Wilderness, Chancellorsville, and the campaigns around Richmond.

By way of contrast, no list of the Home Guards has been preserved in Confederate files except a roster of the commissioned officers as recorded in John W. Moore’s Roster of North Carolina Troops in the War Between the States. According to this reference two companies, B and C, had been organized. The officers for the first named unit were Willis B. Sanderlin, Captain; F. M. Halstead, First Lieutenant; and Enoch Stephens and Willis Morrisett, Second Lieutenants. Only two officers are given for the C detachment, Captain Caleb P. Walston and First Lieutenant William P. Walston. Sanderlin was promoted to field officer with the rank of major in 1864, and was succeeded as company commander by Halstead who had been made captain. Captain Caleb P. Walston was transferred to the command of Company A in the field in 1864, and tradition has it that he was succeeded by William P. Walston who assumed charge of the local units with the rank of captain. But beyond these brief items, definite knowledge is indeed brief. Because of the double hazards represented by the presence of the Federal troops and the local Buffaloes, a policy of extreme secrecy was adopted as to the activities of the Guards, and this reticence was maintained after the war, possibly as a precaution against reprisals should details of their participation become known to the governing officials under carpetbag rule.

Oddly enough, most of the documentary information concerning the home forces is to be found in the reports of the Yankees themselves. Apparently encouraged by dissension that had developed in Company A and among the inhabitants of the lower part of the county, Captain Enos Sanders of the Federal Army seems to have landed a detachment in the vicinity of Old Trap during the month of August in 1862 and, having organized the disgruntled group into a band of Buffaloes, proceeded to occupy Shiloh. That the Home Guards, or “Guerillas” as the Yankees called them, were watchful and biding their time, however, is clearly shown by the following report which Sanders made to his superior, Colonel W. A. Howard:

“Headquarters

Shiloh, N. C., Sept. 18, 1862

“Sir: Last night we were attacked, as we had all the force over to Pasquotank holding a meeting, and stopped overnight, except the gun’s crew, which we sent back, all except 16 men—them we had with us. We got word this morning that the rebels had assembled, and with about 30 men had landed 5 or 6 miles below Shiloh. There are 3 men killed, 3 wounded, and 5 or 6 taken prisoners, and they have taken all the arms and ammunition the men had and stores and provisions. They were completely surprised. The men that got away think their force was about 50 strong. Please send us a gunboat and men immediately; send two howitzers and ammunition for same. We can intercept them at the upper end of the county. It is necessary to have a chance to get reinforcement at Pasquotank. They got all our guns and all our private property. We have the names of some of the rebels. Joseph Forbes was one of the leaders.”

Although a report from Confederate sources could hardly have described a more successful attack than did the Yankee Captain Sanders, our great loss is that no account by the victors is available. An outline of the plans of attack—by whom and how carried out—could hardly fail to be of greatest interest to the descendants of those responsible for the maneuver. There is a tradition of a daring assault at night by a group of teenage-youth who killed three or more Federal soldiers and Buffaloes and temporarily drove the enemy from Shiloh. The leader of this bold band is said to have been the late Willoughby N. Gregory who, however, refused to confirm or deny the truth of the rumor, and indeed the reference could have been to other brushes and skirmishes which took place during the period of occupation.

On September 21, four days after the surprise and capture of Captain Sanders’ men, Captain William B. Avery of the U. S. gunboat Lancer, then riding at anchor off Shiloh, writes of the efforts made by the Union forces to track down and punish the attackers. “I reached Shiloh at 4 p.m. Friday 19th”, he states. “I landed 60 men, taking with me Lieutenants Fowler and Moore, and leaving . . . Sanders with 20 men, we started for the place where the rebels were last heard of . . . in a swamp near the ‘Lake’, as they term a sort of pond.” But when they reached the “Lake” region they learned that the rebels had spent the previous night there and had gone on. He and officer Sanders and twenty of their best men took up the pursuit. The trail led across the battleground near South Mills and on across Pasquotank River by way of River Bridge. One and one half miles beyond the bridge Avery caught up with the Confederates just as they were halting for dinner. According to his account: “Without firing a shot they took their guns and fled to the swamp across a cornfield, leaving muskets and prisoners in our hands.” He was disappointed, nevertheless, because he had not found the howitzer which had been captured at Shiloh.

In April of 1863, Major J. W. Wallis, officer in charge of the Union forces in this locality, writing from Elizabeth City, reported that his command consisted of two companies from Massachusetts, about twenty men from North Carolina and “two armed schooners with 26 men each, and about 100 negroes and laborers.” He relates with evident chagrin the following incident. He sent Captain Sanders down the river with seven soldiers and ten Negroes for wood. The wind blowing so the men could not land to get the wood, they went ashore to visit their families, where they were all promptly captured and sent to Richmond.

An account prepared by Captain Enos Sanders in Washington, N. C., May 1, 1863, contains several items of local interest. On the fourth of April, he reports, he reached the Pasquotank River at five in the afternoon, and: “We landed at the mouth of the river and marched to Shiloh, a distance of 10 miles, where we went aboard the gunboat at 10 p.m. I sent word to the men to be already the next day to go with me.”

“On the morning of the 5th we went to Elizabeth City; landed and got the family of William Wright; went to Shiloh; the schooner Patty Martin had arrived; went to Jones’ Mill; landed, marched to Old Trap; found some of the men collected there, but the others, not knowing of our presence, could not be found. We stayed till morning, and then went on board with 7 of my men as follows: Peter, Stephen, Cornelius and Nicholas Burgess, Ithean and Wilson Duncan, and Dempsey Wright. We crossed over to the Pasquotank side; landed and got the family of Joseph Morgan. There were four men in that County belonging to my company; one, John Cartwright, came with us; one could not be found, and the other two were, one sick and one wounded . . . picked up the family of Mr. Moss and started for Roanoke Island.”

“. . . I left 11 men in Camden, 3 in Pasquotank and 2 in Elizabeth City.”

On the eighth day of the following August, Captain W. Dewees Roberts, commanding a detachment of the Eleventh Pennsylvania Volunteer Cavalry, and stationed at South Mills, describes what was to him a disagreeable experience. On the previous day, he relates, he reached Camden Court House and crossed over to Elizabeth City in a boat with eight men. He went into town, captured one officer and three enlisted men, but “hardly had the boat pushed off” when they were fired upon by “about 20 Guerillas. . . . I pushed for the opposite shore and landed in a swamp.” They remained in the swamp all night and “got to Camden Court House the next morning”. In his opinion there were four companies of Guerillas in the Albemarle region; one in Camden, one in Pasquotank “with headquarters in a swamp near Elizabeth City,” one in Perquimans and the fourth in Chowan.

The activities of the Guerillas, employing the term used by the Yankees, must have been a source of continued irritation to the enemy, for in the early fall of 1863 Lieutenant Colonel William Lewis of the Fifth Pennsylvania, whose headquarters were at Great Bridge, Virginia, describes another incursion through Currituck and on into Camden by way of the bridge at Indiantown. According to his account: “When the advance arrived in sight of the bridge, a squad of 30 or 40 guerillas were discovered on the bridge, but immediately fled to the woods on the approach of our forces. The swamp was skirmished and shelled (a howitzer having been taken with the expedition), but without effecting anything. The column passed 3 miles beyond the bridge to Major Gregory’s house, and there halted, after carefully scouting the country in every direction, but without finding the enemy which was known to be there about 300 strong.” At this point one suspects the officer’s imagination was exaggerating the strength of the Guerillas, since his report records no other evidence of numbers other than the “30 or 40” seen on the bridge.

“Lieutenant W. E. A. Bird,” he continues, “was then sent to arrest Silas F. Gregory, a notorious guerilla, but he has protection from Major General Foster. He is engaged in arming and feeding the guerilla bands in the vicinity. Lieutenant Bird, in proceeding to the house, used every precaution, by dismounting his men as skirmishers through the woods. But after making the arrest on his return was less cautious, as the distance was but a mile, and had been skirmished over but half an hour before. This resulted in his receiving a volley from the woods, killing 1 man and wounding 2 severely. Lieutenant Bird’s horse was wounded; also one belonging to Company L.”

“At the alarm all the forces were immediately put in motion and the woods thoroughly skirmished, but without finding any of the assassins. During the attack on Lieutenant Bird, Silas F. Gregory succeeded in making his escape. The farmers in the neighborhood of the swamp were all notified to clear away the underbrush skirting the road, under the penalty of having their property destroyed. After this the command marched without a single incident.”

The foregoing incident reveals interesting information and excites our curiosity as well. The closing remarks seem to indicate that the Federal forces had not as yet adopted a policy of destruction which the county was to suffer a few months later. We wonder what, and why, was the protection afforded Silas F. Gregory, a noted Guerilla, by a high ranking officer of the United States Army.

A few weeks afterwards, October 20, a Union cavalry detachment numbering forty, commanded by Major McCandless, was fired upon from ambush “about four miles from Camden and eight miles from South Mills,” and two privates were killed and one wounded.

Another invasion late in 1863 ushered in a period of great destruction and distress. A Federal detachment from Virginia first marched to Elizabeth City by way of the canal road through the Great Dismal Swamp. A description of the journey was portrayed with realism by the commanding officer who thus wrote: “We were in the dreariest and wildest part of the Dismal Swamp, the darkness was dense, the air damp, and the ghastly silence was broken only by the hooting of owls and crying of wild cats. For two hours we rode through the Stygian darkness of the forest, when we arrived at South Mills—a collection of about twenty houses—where we stopped to rest our horses. Here we left the canal and descended into another swamp of Hades. The narrow crooked road was flooded with water and crossed with innumerable little rickety bridges, over which our horses picked their way with great caution and reluctance”. In Elizabeth City contact was made with General Wild’s headquarters, and then a foray was made against the Guerillas in both Pasquotank and Perquimans counties.

General Edward A. Wild’s official account of the situation, written at Elizabeth City, December 12, 1863, to General Barnes, reads as follows:

“I have the honor to report that we occupy this place, and thus far without accident. Below South Mills we built a solid bridge on the piles previously standing, but partly burned, and marched hither.”

“Our two steamers, I. D. Coleman and Three Brothers, arrived beforehand, and lay off out of sight, but signals from our cannon brought them up. They are now unloaded, and in use for other purposes. A gunboat has made two calls here very recently, having quite a salutary influence in confirming our footing here. But I would be glad to keep one around as long as we stay. At her last call she carried off a steam mill and machinery, some said for Roanoke some for Fort Monroe. We keep hearing of considerable bodies of State partisan rangers, alias guerrillas, but not strong enough to harm us. All we dread is the sending of a regular force from Suffolk, Winton, or even from Richmond.”

“I have sent out today four expeditions hence, one to Hertford for contrabands, etc; one in search of guerrillas; one for forage for our cavalry and artillery; one for fire-wood, which we need much—this party takes the lightest steamer up the river, also, I am just sending the other steamer down to Roanoke Island with a load of contrabands, including horses and carts, on a schooner in tow, to return with a load of coal for both steamers. Thus every man is emplyed.”

Then the expedition or, as another report reads, “The Army of Liberation” under General Wild proceeded to Camden County by way of Indiantown, collecting on the way a large number of slaves, horses and mules. “While this was going on,” the narrative states, “the farms were foraged to some extent. Geese, chickens and turkeys everywhere abounded, and the inhabitants being all ‘secesh’ the men were permitted to help themselves.” With the fowls collected the soldiers prepared themselves a great feast at the elegant residence of Dr. Gideon Marchant, who lived in Currituck near Indiantown Bridge, and there they camped for the night.

The statement continues: “As before stated a force of 400 men had been sent from Elizabeth City, under the command of Col. Draper of the Second North Carolina, to scout the lower district of Camden County for contrabands, with orders to unite with the main column at Indiantown. The region was found to abound with fine plantations, and the result of the first day’s ‘canvass’ was twenty team. Encamped that night at Shiloh—a village of about twenty houses and a church—fires were built at a crossroad near the church, while the men were quartered in the church, and pickets quartered on all the approaches. About midnight the pickets were driven in by a force of guerillas, supposed to number about 100 men, who discharged their rifles at the campfire, where they supposed the men to be sleeping. This was what Colonel Draper had anticipated, and thanks to his shrewdness not the least harm was done. The fire being returned by the reserved guard, the guerillas fled into the swamp. The next day resuming the march to Indiantown at a place called Sandy Hook, where the road crossed a swamp they were attacked by a large body of guerillas in ambush. Col. Draper ordered his men to lie down while loading their guns, and sent two detachments to attack the bushwhackers with bayonets on both flanks, skirting the woods for protection. . . . the detachments had reached the woods in which the guerillas were posted, when, perceiving that they were flanked, they took to their heels and escaped by a path which the Colonel’s men could not find at the time. The fighting lasted about half an hour. Col. Draper lost 8 killed and 7 wounded. The loss of the guerillas, as was ascertained, was 13 killed and wounded.” This section of the report ends with a statement that upon entering Indiantown his rear guard was fired upon “and one man killed.”

It seems clearly evident from the preceding information that the invaders were continually harassed by a band which they estimated to be one fourth of their own strength. If a report were available as to the methods employed by the local company, whose size was actually more nearly fifty than the figure estimated, this march from Shiloh to Indiantown would doubtless constitute an exciting tale. Since we are not sure of the names of leaders even, the missing details must be supplied from our imagination.

When contact was effected with General Wild at Indiantown, he attempted to subject the neighboring inhabitants to an especial humiliation, seemingly to indulge his sadistic sense of enjoyment.

The Pasquotank Guerillas, according to the official explanation, “had fought shy of the armed ‘niggers,’ invariably skedaddling at their approach, but as those of Camden seemd more bold and numerous, Gen. Wild determined to return to Sandy Hook, and ascertain if the ‘State Defenders’ were really sprouting for a stand-up fight with an equal number of colored boys.” Accordingly, the next morning—leaving behind sufficient force to protect the camp—the General started for the “Hook,” taking with him about 400 men. “A half mile from Indiantown the guerillas were decried ahead.” Colonel Draper, who commanded the advance, at once started his men on the “double-quick” for them, “when firing a few shots they turned and fled.” The next remarks seem to express the General’s emotions: “The main column led by General Wild, on foot, immediately joined the chase, and a singular spectacle for Jefferson Davis to contemplate was presented; his unconquerable chivalry—any one of whom used to be called equal to six or eight picked yankees, running for dear life from the bayonet of despised ‘niggers.’ O Jeff!” “The colored boys,” it is added, followed “some distance behind filling the air with eager shouts.” All trace of the Guerillas was lost “at the edge of the impassable swamp”.

After a long search they found a zigzag path, cunningly arranged, and by following this trail they discovered the camp of the Guerillas. Then the report gives a detailed description of the scene: “Here, surrounded by gloom and savage wilderness, was spread the camp of the guerillas, consisting of log huts and a number of tents. Fire was burning, Enfield rifles scattered over the ground and everything indicated a hasty evacuation of the place. Between fifty and sixty rifles, a drum, a large quantity of ammunition of both English and rebel manufacture, clothing, a tent full of provisions, and, lastly, the muster roll of the company fell into our hands. The huts were soon in flames and the camp of Sanderlin’s land pirates vanished into smoke. . . . which rose in vast black volumes above the forest.” After the Yankees returned from the woods they came to a large farm house belonging to Major Gregory. And, “it having been ascertained that Sanderlin obtained here a considerable portion of his supplies,” the house, containing “several thousand bushels of corn,” was burned and Gregory was carried away a prisoner. “Guided by the captured muster roll, all the dwellings belonging to the guerillas within four miles were burned.” General Wild returned to Indiantown “not so well satisfied with his morning’s work as he would have been had the villains dared face his colored troops.”

Two items mentioned in the description of the camp in the swamp are of especial importance to the Civil War history of this county. Here is found the most pointed documentary reference known as to the activities of Willis B. Sanderlin in Guerilla warfare. In one other Federal report he is cited along with “Elliott, Etheridge, Hughes, Grandy and Walston” as being among the Guerilla chieftains assembled at Hertford. The persons named were all presumably from Camden, and this is the only notation found referring to William P. Walston. The first names of the others are a matter of guesswork. An equally interesting tidbit in the account is the information concerning the captured muster roll. This fact suggests the possibility that it may still survive in some Northern collection of war mementos.

A circumstance also arousing our curiosity in General Wild’s narrative is his failure to explain why one dwelling was not destroyed, since, as we have previously noted, the occupant had already been considered “a notorious guerilla.” The homes of his adjoining neighbors, Major Gregory and Luke Stevens, were reduced to ashes, but the house of Silas Gregory was mysteriously spared, and today, incidentally, is a well-preserved structure.

General Wild’s determined efforts to stamp out the Guerillas, who were also referred to as “partisan rangers,” are proof enough that even though their numbers were but a fraction of the Union forces, those Home Guards were constantly inflicting losses upon the invaders, who remained in a state of anxiety. The march of the invaders from Shiloh to Indiantown and their immediate return through Sandy Hook took place within three days, beginning with December 20. At the same time the headquarters of General Benjamin F. Butler, whose harshness incurred the lasting resentment of the inhabitants of this area, was also keeping a watchful eye upon developments in the Albemarle region, as may be inferred by the following three dispatches from George W. Getty to General Butler.

December 21

“If Wild is in Currituck County, it would be well to send a steamer to Pongo to be in readiness to transfer the Ninety-eight New York from that place to Coinjock Bridge or Northwest Landing, as may be most needed. I have sent a squadron of cavalry to South Mills to obtain information and watch the movements of the enemy. Commanders of posts have been instructed to afford all possible assistance to General Wild.”

December 22

“. . . On Wednesday and Thursday of last week, a considerable force advanced from Blackwater, passing through Gates County, N. C. for the purpose of opposing the march of troops under Generald Wild, who, it was reported, intended marching from Elizabeth City upon Hertford, Edenton, &c., and thence through Gates County to Suffolk. A portion of this force advanced as far as the Pasquotank, and after destroying the bridges, ferries, &c., returned.”

“To draw attention from the force sent against Generald Wild, infantry and artillery were concentrated at each of the points, Franklin and Zuni, for the purpose of making a demonstration in the direction via Suffolk. The force at Franklin advanced as far as Carrsville. Of that at Zuni I have no information. No doubt the movement was suspended in consequence of the withdrawal of General Wild’s force to the east side of the Pasquotank. All is quiet at Suffolk and South Mills tonight.”

December 23

“Lt. Col. Stezel, commanding outpost of Suffolk, reports this morning that there were sixteen companies of rebel cavalry in Suffolk last night from 9 to 11 o’clock, at which time they retired. They came from Elizabeth City to Suffolk, and have gone back to the Blackwater.”

The chief purpose of federal forays in the Albemarle country was to reduce, destroy or immobilize the daring and troublesome Guerilla bands. And in truth these brave home defenders were being reduced to helplessness. How this end was finally accomplished by the conquerors, for all practical purposes, is clearly set forth in General Butler’s report from “Fortress Monroe,” December 31, 1863, to Secretary of War, Edwin M. Stanton, and which is herewith quoted:

“I have the honor to report that General Wild was dispatched by my order upon an expedition with two regiments of colored troops into the northeastern counties of North Carolina. Our navigation on the Dismal Swamp Canal has been interrupted, and the Union inhabitants plundered by the guerrillas.”

“General Wild took the most stringent measures, burning the property of some of the officers of guerrilla parties, and seizing the wives and families of others as hostages for some of his negroes that were captured, and appears to have done his work with great thoroughness, but perhaps with too much stringency. The effect has been, however, that the people of Pasquotank, Currituck, Camden, Perquimans, and Chowan Counties have assembled, and all passed resolutions similar to those which I enclose, which were passed by the inhabitants of Pasquotank County, and three of the counties have sent committees to me with their resolutions. These resolutions were signed by 523 inhabitants of the county, an average vote being 800, and every prominent man, I am informed by the committee who presented them, that had not signed them had left and gone across the line.”

“The guerrillas have also been withdrawn from these counties, to the relief of the inhabitants.”

“I have promised the committees of the several counties that so long as they remain quiet, keep out the guerrillas, and stop blockade running, that they shall be afforded all possible protection by us, and be allowed to bring their products into Norfolk and receive goods in exchange.”

“Until I can get sufficient force organized to make it safe to throw my lines around them, I have further informed them that I shall not require the oath of allegiance.”

“I think we are much indebted to General Wild and his negro troops for what they have done, and it is but fair to record that while some complaints were made of the action authorized by General Wild against the inhabitants and their property, yet all the committees agree that the Negro soldiers made no unauthorized interference with property or persons, and conducted themselves with propriety.”

“I find some of the officers in the department in command of white soldiers, a considerable degree of prejudice against the colored troops, and in some cases impediments have been thrown in the way of recruiting, and they were interfered with on their expeditions. This I am investigating, and shall punish with the most stringent measures, trusting and believing my action will be sustained by the Department. I also find some incompetent officers in the negro regiments. . . .”

“I shall take leave, therefore, to report for dismissal those who in my judgment, upon investigation, are not fit for service. The Negro troops, to have a fair chance, ought to have first-class officers. . . .”

“I beg leave to inclose a copy of General Wild’s report, and also the original proceedings of the citizens of Pasquotank.”

While no record of a meeting in Camden for the purpose of adopting the resolutions referred to by General Butler seems to have been preserved, doubtless the proceedings were similar to those of the Pasquotank gathering. What took place in that county is described in an enclosure attached to General Butler’s communication to Secretary Stanton, and from which the following quotations are taken.

“Petition of 523 citizens of Pasquotank”

“At a meeting of the citizens of Pasquotank County, N. C., held at the court-house in Elizabeth City, December 19, 1863, Dr. William G. Pool being called to the chair and Isaiah Fearing selected secretary, a committee consisting of George W. Brooks, John C. Ehringhaus, R. F. Overman, William H. Clark, and (by motion) William G. Pool were appointed to present suitable matter for the action of this meeting.”

“Being called upon, George W. Brooks, chairman, submitted the following preamble and resolutions, which were unanimously adopted:”

“Whereas the county of Pasquotank has suffered immensely since the fall of Roanoke Island, without aid or protection from any source: and whereas we have been lately visited, by order of General Benjamin F. Butler, by such force and under such circumstances as to cause universal panic and distress; and whereas we have been assured by General E. A. Wild, in command of the force, that he will continue to operate here, even to the destruction, if necessary, of every species of property for the purpose of ‘ridding this country of partisan rangers’; and whereas we believe that these rangers cannot be of any service to us, but that their further presence here will bring upon us speedy and inevitable ruin; and whereas we are promised to be ‘let alone’ if these rangers be removed or disbanded and return quietly home, and further, if that species of business known as ‘blockade running’ be desisted from: Therefore, in view of these facts and of this condition of things,”

“Resolved, That we earnestly petition the Governor and Legislature of North Carolina, satisfied that you cannot protect us with any force at your command, to remove or disband these few rangers; on motion,”

“Resolved, That we denounce that species of business carried on here by private citizens for private gain known as ‘blockade running’; and that we hereafter use our best efforts to suppress such trade.”

“On motion, Barney Berry, Dr. J. J. Shannonhouse, John D. Markham, Thomas I. Murden, B. F. Whitehurst, Timothy Hunter, Frank Vaughan, and D. D. Raper, being one of each captain’s district in the county, were appointed to obtain the signatures of every male citizen of the county above, and to send copies to the Legislature of North Carolina and to General B. F. Butler.”

“On Motion, William H. Clark, Dr. J. J. Shannonhouse, and Richard B. Creecy were appointed a committee to bear these proceedings to the Governor and Legislature of North Carolina, and to ask their immediate attention to the same.”

“On motion, a committee consisting of George W. Brooks, George D. Pool, and John J. Grandy was appointed to bear the proceedings to General B. F. Butler, at Fort Monroe, and to learn of him whether the removal of partisan rangers from this county, and the ceasing of all persons in this county to run the blockade, will secure us, through him, from raid by United States forces through this county and the further destruction of our property.”

“On motion, George Brooks, W. F. Dashiell and Reuben F. Overman were appointed a committee to raise funds to defray the expenses of the committee to Raleigh and Fort Monroe.”

“On motion, the following persons were appointed to bear the proceedings of this meeting to the following counties, viz; Charles C. Pool to Chowan; Andrew J. Perry, to Gates; John H. Perry, to Perquimans; J. B. Shaw to Camden; and C. L. Cobb to Currituck.”

“Meeting adjourned.”

“Signed by W. G. Pool, Ch. Isaiah Fearing Sec. Benoni Cartwright, John W. Graves, Jesse M. Rhodes, Charles Meeds, Marmaduek Rhodes, James Gannon, Barney Berry, et al. Elizabeth City, Dec. 26.” The scarcity of written materials relating to the civil conflict in this county is offset in part by an abundance of traditions. By this means stories of many incidents have been handed down, and some gain fresh details as the years go by. One of the best established tales concerns a courageous journey in the night by young Wealthy Burgess who, although a sister of the Buffalo leader, Peter T., was a staunch supporter of the Confederacy. Late in the war a small group of captured Confederate officers, who were being transported via these inland waters to a northern prison, by a strategem effected a mutiny on the boat and escaped to the protection of North River Swamp, where they were forced to remain in hiding. A rigid supervision already maintained by Union patrols was now intensified as every road was watched for traces of the escaped prisoners. Samuel Leary of Sandy Hook furtively supplied them with food at the risk of death, loss of property, and danger to his family. Indeed, an effort by any man with Confederate sympathies to guide the officers to freedom would clearly invite disaster both for them as well as for himself. By underground channels, however, arrangements had been made to provide escape on one of the fishing boats lying in Pasquotank River. Since the officers were unfamiliar with the country, their problem was to travel undetected from North River pocosin and across Camden County to the waiting sailboat on the river. Believing the Yankee search parties were less likely to suspect a woman, Wealthy Burgess volunteered to act as guide. As night came she left the house of a relative living at Taylor’s Beach along the Pasquotank River and, avoiding the roadways, traversed eight miles mostly through forests and swamps to the waiting officers. Retracing the route, she conducted them to the waiting fishing smack, which slipped safely away in the darkness.

Among the many episodes occurring, there were some which emphasized the tragedies of war more poignantly than death in combat even. For example, when the Home Guard, John Bell, was fatally shot from ambush, two women weaving cloth a half mile away heard the noise of the discharge with misgivings; such a sound had come to mean, they had learned, that a human being was the target and not a wild animal. Knowing that no man from the opposing factions could safely investigate, they harnessed a horse to a two wheeled cart and, following a path, found the recently killed man lying across a footlog. Conscious of a certain dignity due the dead, Mrs. Mary Kight and young Sarah Burgess lifted the body into the farm vehicle and thus transported it to his dwelling, a distance of some three miles away. When the war was over, the soldier who returned from the distant battlefield, the Guerilla and the Buffalo—all attempted the difficult task of making a living under the trying regime of reconstruction. Willis B. Sanderlin resumed his business as a merchant in Shiloh, and he also operated his plantation known as the Bear Garden. William P. Walston began farming again. Later, he became somewhat active politically, representing Camden in the lower house in 1891.

By a coincidence, both men removed from the county. Major Sanderlin disposed of his various properties and migrated to Virginia. Captain Walston suffered financial reverses and spent his last days in Pasquotank. It is to be hoped that further information will eventually be discovered to give us more details of their leadership in the various exploits of the Home Guards or Guerillas.

Source Three Hundred Years Along The Pasquotank by Jesse F. Pugh pages 173 – 188