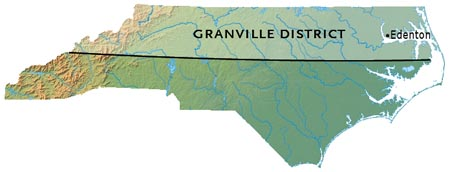

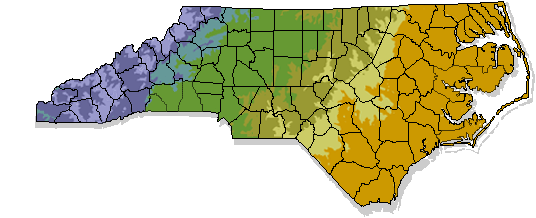

Compare the two maps above, and you will see that Old Guilford County (present-day Guilford, Rockingham, and Randolph counties) was in the Granville District. If you view the maps of North Carolina County Formation, you will see that there is a straight line dividing Rowan and Orange from Anson and Cumberland in 1760. In the 1775 county map, the straight line continues, dividing the northern half of the western part of the state from the southern half of the western part of the state.

(Above) Today, the Granville District southern boundary can still be seen in certain NC piedmont county boundaries, with minor variations in places. It is reflected in the line that crosses west to east dividing Iredell from Mecklenburg, Rowan on the north from Cabarrus and Stanly on the south, and Davidson and Randolph and part of Chatham on the north from Montgomery and Moore counties on the south. The Granville line was extended into the mountains in 1772, when the boundary between NC and SC was being surveyed, but no western grants were based on that later survey, and therefore it did not play a role in forming county boundaries in that part of the state. Modern county boundaries in the mountains and foothills, and the sandhills and the coastal plain, reflect the land’s topography and rivers, which are the natural and usual boundaries between counties and different areas in a state.

THE HISTORY OF THE GRANVILLE DISTRICT

Granville District was a sixty-mile-wide strip of land crossing the colony of North Carolina next to the Virginia boundary. North Carolina was a proprietary colony originally, with eight Lords Proprietors owning the land from 1663 to 1729. In 1729, seven of those eight lords were persuaded to sell their land back to the English Crown. The eighth Lord Proprietor at that time was John Carteret, Baron Carteret of Hawnes in the County of Bedford; and he refused to sell his share back to the Crown, although he never visited his land in North Carolina during the course of his lifetime.

Originally, he was entitled to one tract of land in NC, a second tract of land in SC, and yet another in GA (all of which were originally part of “Carolina”). Samuel Warner, a London surveyor, was hired to calculate the size that one continuous tract would be, and he determined that Carteret’s one-eighth share should be from the northern boundary the current VA/NC line (36 degrees 30 minutes), and the southern boundary 35 degrees 34 minutes. In 1743 the initial boundary line was surveyed by a commission. The line was extended westward in 1746, and again in 1753. The sixty-mile-wide tract of land was to extend from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. Those landowners who had already received grants of land within the new tract from the Crown or the other Lords Proprietors were to retain their grants, but now they had to pay an annual quit rent to Lord Carteret.

From 1729 until 1744, he took one-eighth of the quit rents for North and South Carolina. In 1740 and 1744, Lord Carteret appointed two agents, one for handling land grants, and one for receiving quit rents, as he started forming plans for the land office in North Carolina. The system that he and his solicitors and advisors devised did not include headrights. A man could purchase as much available land as he could afford, but each purchase of land could not exceed 640-700 acres. The usual maximum grant was 640 acres, or one square mile. There was a system of fees for each step of the process, which went from written application for an entry, to the issued warrant for a survey and plat, to the grant of the actual deed. These were deeds in fee simple.

Meanwhile, in 1744, Carteret had inherited the title of “2nd Earl of Granville,” and the district became known as “Granville District.”

Royal Governor Gabriel Johnston, and later Royal Governor Arthur Dobbs had concerns about the accuracy of the survey for Granville District, even going to the point of hiring their own surveyors to check measurements, and Dobbs argued that the line had been run as much as over thirteen miles too far south. There was also some resentment over the size of the district, which was nearly half the land in North Carolina. Part of this had to do with the fact that the royal governor was responsible for the land’s government, but he did not receive any revenue from it.

Around 1750, Granville became concerned over discrepancies in the account books kept by his agents in the process of issuing land grants; and he spelled out detailed instructions regarding records and grants. Despite this, complaints of inappropriate fees from landowners and prospective clients increased during the 1750’s.

The Granville District land office was open from 1748 to 1763, and it was located in Edenton for most of that time. The agents were supposed to travel the District Superior Court circuit, attending those when they were in session, going from Edenton to New Bern to Halifax to Hillsborough to Salisbury.

Meanwhile, Henry McCulloh had received a royal grant of a large tract of land, some of which was within Granville’s District. Granville gave McCulloh permission to settle his land. However, in 1752 it became apparent that Granville’s agents had issued grants within McCulloh’s land, and a series of disputes began, culminating with the State of North Carolina confiscating McCulloh’s land in 1779.

Granville died in 1763, and the Granville land office closed in 1763, never to open again. Granville’s son Robert, 3rd Earl Granville, inherited the land, but the will’s terms did not give him control over it. The agents continued to accept entries for land from 1763 to 1776 , but they issued no warrants, no surveys were made, and no deeds were granted.

The 3rd Earl Granville considered selling the land back to the English Crown, but he never actually completed the transaction, and the situation continued to become more difficult, as records were not kept accurately, and settlers were unable to obtain clear title to their lands. This in turn led to outbreaks of violence in 1770; one of the outcomes of this being the Battle of Alamance. Governor William Tryon sent troops to the area to calm the situation. By the time the younger Granville died in February 1776, the Granville proprietorship was seen as representing British interests, during the time immediately prior to the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. In 1777, the North Carolina assembly declared the new state sovereign over all lands between Virginia and South Carolina, though it did recognize claims to land granted by the crown and proprietors before July 4, 1776. It later confiscated all lands and property of persons who supported the British Crown during the Revolutionary War.

Material was gathered from Margaret M. Hofmann’s introduction to her series of abstracts on “The Granville District of North Carolina, 1748 – 1763,” and other sources.